Geography

Modern Franklinville is made up of two initially independent mill villages, Franklinsville and Island Ford, separated by about three-quarters of a mile of Deep River. The developed area of the village was defined by Deep River on the south and southwest; Walnut Creek running into the river from northwest to southeast; and Bush Creek on the west trending down into the river. The community perched on the terraced slopes of the hill embraced by these watercourses, and was accessible without crossing water only along the narrow northwest ridge of land between Bush and Walnut Creeks.[1] The original Franklinsville mill village was developed by the corporation beginning in 1838, and its cultural landscape was stratified in a manner that reflected its physical geography.

On the lowest level, just above the floodplain of the river, were the mills which provided the economic backbone of the village, together with their ancillary warehouses, storehouses, and barns. On a level about five feet above the mill, the company store and company boarding house were located to the north; to the south and across the mill race were the homes of the miller and company president. North of the store on a terrace about fifteen feet higher was the Cotton Row, housing built by the mill for the workers. At least six and perhaps more of these houses were built as part of the initial mill construction in 1838, all of a similar size and plan. About ten feet higher still, and trending northwest up the hillside, were located the larger homes of tradesmen, craftspeople and professional men such as Doctor Phillip Horney. The lots higher up the hill had been sold privately to friends and family members by Elisha Coffin, promoter of the factory and owner of all the acreage around the mill. Lots for public institutions such as the school, meeting house, cemetery and town hall were located near the top of the river-front arm of the hill, with stores fronting the road leading north toward Greensboro. At the crest of the hill was situated Elisha Coffin’s own house, surrounded by its community of “dependencies”—office, kitchen, smokehouse, well house, icehouse, dairy, animal sheds, stable, barn, and servant houses.

Housing

Settlers began to arrive in the eastern half of what would become Randolph County in the late 1740s, and were entering applications for land grants soon thereafter. A community began to grow up along the stretch of Deep River between Bush and Sandy Creeks by the early 1760s. The first known settlers were Solomon Allred (1752) on Sandy Creek and William Allred (1762) on Bush Creek, with a blacksmith named Hercules Ogle (1759) on the south side of the river between them. A Virginian named Jacob Skeen settled in the Walnut Creek area on the north side of the River around 1770. Skeen was evidently a miller and began the first improvement on the river; his petition to buy land from the state in 1778 referred to his “mill seat”. By 1793 Skeen was dead and his mill was in disuse; it was sold to three other millers over the next 8 years, until completely rebuilt by Christian Morris (Moretz) in 1801.

The recorded history of the community certainly dates to the construction of that 1801 Morris grist mill, and a dwelling located on a hill southwest of the grist mill probably dated to this early period. It was torn down in the 1950s when the hill in that area was leveled for roller mill parking. Morris and the other millers undoubtedly lived close to the mill itself, but other settlers began moving up the hill, safely out of the range of flooding. The earliest domestic survival from this early period is the Cornelius Julian House, said to be dated 1819 on an inscribed foundation beam. During this earliest period the Julian House undoubtedly had the aspect of a self-sufficient farm house, with detached kitchen, smokehouse, stable, barn and other ancillary buildings, together with extensive gardens and pastures. In the 1830s it was evidently being used as a tavern or inn along the Raleigh-Salisbury stage road through the village.

The first houses built by the mill are now known as the ‘Cotton Row’ houses, four remaining one-story houses and one two-story house, which now have West Main Street addresses, but at the turn-of-the century were considered to front on Railroad Avenue, a street which paralleled the railroad tracks and the river. Those houses were 2 rooms downstairs, with a loft on the second half story. Early census records indicate that there were as many as seven to ten people living in each of these houses, not only entire families, but including various boarders. This goes to show the changes that have occurred in American society over the past 150-200 years regarding personal space. People at that time had fewer personal possessions and thought nothing of sharing beds with other family members and even strangers, when necessary. This is similar to the communal living and sleeping arrangements exhibited by modern-day third-world countries and migrant workers.

The larger two-story houses passed during the early settlement period of the mill village were predominately built by craftspeople. The blacksmiths, tinsmiths, potters, cabinetmakers, coopers, wheelwrights, wagon-makers, and other tradesmen listed in census records as working in the village would have engaged in their commercial activities in small shops adjoining their homes. But even the owners of these more middle-class residents took in boarders, just as did the millworkers down the hill, to make financial ends meet.

Service Buildings

While it is not clear whether these Cotton Row houses had individual detached kitchens, each one would certainly have had a collection of several small outbuildings necessary for food storage and personal hygiene. Most importantly, every home had its individual outhouse. The usual practice on farms and rural lots was to move the location of the outhouse every few years so as to prevent the saturation of the drainage capacity of one particular spot. However, on small lots in urban situations such as Franklinville, the outhouses were instead periodically cleaned out by hired labor. In Franklinville at this period, this job was done by a black man, who on a contract basis would clean out the cesspit and cart away the wastes.

Another common outbuilding was the smokehouse, where preserved meats would be cured and stored pending use by the family. Water pumps were evidently a communal feature shared by several houses, as were stables and cow sheds. However, every house had its own garden plot, which probably included mixed plantings of vegetables and flowers. It is unclear to what extent worker gardens included ornamental plantings, but it appears likely that a standard feature of each house would have been some sort of ‘swept’ yard, which provided the work areas required for food preparation, laundry, and etc. Swept yards have been recognized in the 20th century as characteristic of African-American houses, but this is a holdover from earlier standards features of both white and black householders.

Pedestrian Orientation

Up to the post-World War II era, walking was the predominant method of transportation. Wealthier residents could afford horses, mules, wagons or carriages; later on in the period, similar individuals would purchase automobiles. But by and large people walked everywhere, to work, to the store, to church, to school, and walked these routes several times each day. According to interviews with residents, there was a network of footpaths all over town, connecting each neighborhood to important institutions such as the mills, stores, schools and churches. Records indicate that these paths were sometimes publicly graded and maintained with gravel and fill dirt in the same manner as were public streets. But by and large these paths were those recognized as both necessary and convenient by the community, using consensual pedestrian rights-of-way across common lands owned by the mill and private landowners. Although at the time under consideration there may have been as much or more privately owned property as mill owned property, a backlash of public disapproval would have greeted any attempt by a private owner to close access to one of these paths. Margaret Williams describes a complex network of alleyways going through the backyards of houses between Depot and Rose streets, alleys which everyone used for all purposes. Her description is reminiscent of the public access points and paths which connect local streets to public beaches in coastal communities.

One element which is almost completely missing from the present-day landscape are the fences which separated each domestic unit and its garden from its neighbor. As opposed to modern fencing, normally erected to keep something—children, dogs, pets, whatever, inside an enclosed area; earlier fencing was erected to keep wandering livestock and wildlife OUT of the enclosed area. This reversal of the function of enclosure began in the 1880s, when stock law elections allowed each county township to decide whether animals should continue to wander freely between unfenced tracts. When voters passed a stock law election, owners were required to fence in their pastures and maintain their own livestock. Gates erected where public roads crossed township borders, and the entire township was fenced to prevent strays from wandering into the stock law area. Franklinville township passed such an election around 1892.

Transportation

In mill villages in general and in Franklinville in particular, the pattern of private ownership of property subject to its communal use and enjoyment continued until 1971, when the mill corporation sold the last mill houses and large undeveloped tracts between streets and around the villages into private ownership. The network of footpaths through the village needed to walk to work, crossing creeks and hollows on bridges and footlogs, running from street to street without regard to ownership, survived as long as the mills ran their regular schedule. Maintenance of these paths and roads during the nineteenth century was a legal duty of every able-bodied “poll” (tax-paying male property owners), who was required to do work on the roads in his community every month, or else pay a substitute to work in his place. Such communal road maintenance survived until the 1880s, when the county commissioners began to subcontract road maintenance and construction. The system of county maintenance survived until the Depression of the 1930s, when the State of North Carolina took over maintenance of all county roads. The only remaining local control over roads is given to municipalities through the “Powell Bill,” a state law named after its sponsor, which allocates each municipality a portion of the state tax of gasoline to build and maintain local streets, sidewalks, curbs and gutters.

Bridges have been an absolute requirement of the Franklinville community since its beginning. In 1845 the justices of the Randolph County Court authorized construction of covered bridges across Deep River at both Cedar Falls and Franklinsville. The single-span Cedar Falls bridge was finished in 1846 at a cost of $1272. The longer double-span Franklinsville bridge was contracted to Thomas Rice, a county justice and builder. After suffering several delays, the bridge was completed in May, 1848, at a cost of $750 for the carpentry work and $349 for additional stone masonry. The bridge utilized a Towne “lattice truss” system with king-post trusses for secondary bracing.

Other small bridges, both covered and open, existed around Town on Sandy Creek, Bush Creek, and Walnut Creek. Some of these watercourses retain bridges; others have been channeled into concrete pipes and culverts. Madison N. Brower of Buie Lane in Frankinville was frequently hired by the county during the late 19th century to design, build or repair bridges, both covered and otherwise. In 1901 the Virginia Iron and Bridge Company of Roanoke received a contract to build a three-span iron bridge across the river at Island Ford. The bridge was a gift to the citizens of FV by mill owner Hugh Parks. It was demolished in 1969 in preparation for an expansion of the Lower Mill weave room, which never occurred due to the subsequent death of John W. Clark.

The nineteenth century’s major transportation innovation arrived in Franklinville in 1889, when the “Factory Branch” of the Cape Fear and Yadkin Valley Railway was built into Town. This branch line originated in Climax on the railroad’s main line from Sanford to Greensboro and terminated at a turntable in Ramseur. Trains ran on the line at least twice each day, and included passenger as well as freight service. Special excursions would run to the beaches and the mountains in the summer months, together with daily trips to Greensboro and points north. Passenger service was discontinued in the mid-1950s, and the depot was demolished in the early 1970s.

One of the first automobiles in Franklinville was a 1912 Overland owned by mill superintendant George Russell. Private automobile ownership gradually increased from this beginning, but did not become prevalent until the late 1940s. After World War I, Ford model-T delivery trucks replaced the teams of oxen maintained by the mill. Beginning in the 1930s the R and R Bus Company provided transportation from the mill villages along Deep River, into downtown Asheboro and back. This was seen by village residents as a valuable service providing both independent freedom of movement and entertainment, especially during the World War II era. The bus line was a private operation owned by J.D. and Arthur Ross, and was discontinued in the late 1950s. From that time to the present no public transportation options have existed for the Franklinville community.

Public Services

Hugh Parks the elder had been Mayor of the town at least by 1876, when government expenses paid for little more than a local constable and street maintenance. Town government retained this minimalist character for most of the Twentieth Century. Modern municipal politics date from just before World War I, when a petition effort began among local residents, led by Hugh Parks, Jr., to revive the moribund town government. The Town received a revised charter from the State in 1917, and a Mayor and Board of Commissioners was elected to supervise Town affairs. During the 1920s the Town Government Town officials refused invitations to join Ramseur in building a joint water treatment system on Sandy Creek during the Depression, as mill owner John W. Clark had visions of building his own system on Bush Creek. This never happened, and Franklinville only built and began operation of a municipal water distribution system in 1978, with the benefit of a Farmer’s Home Administration loan.

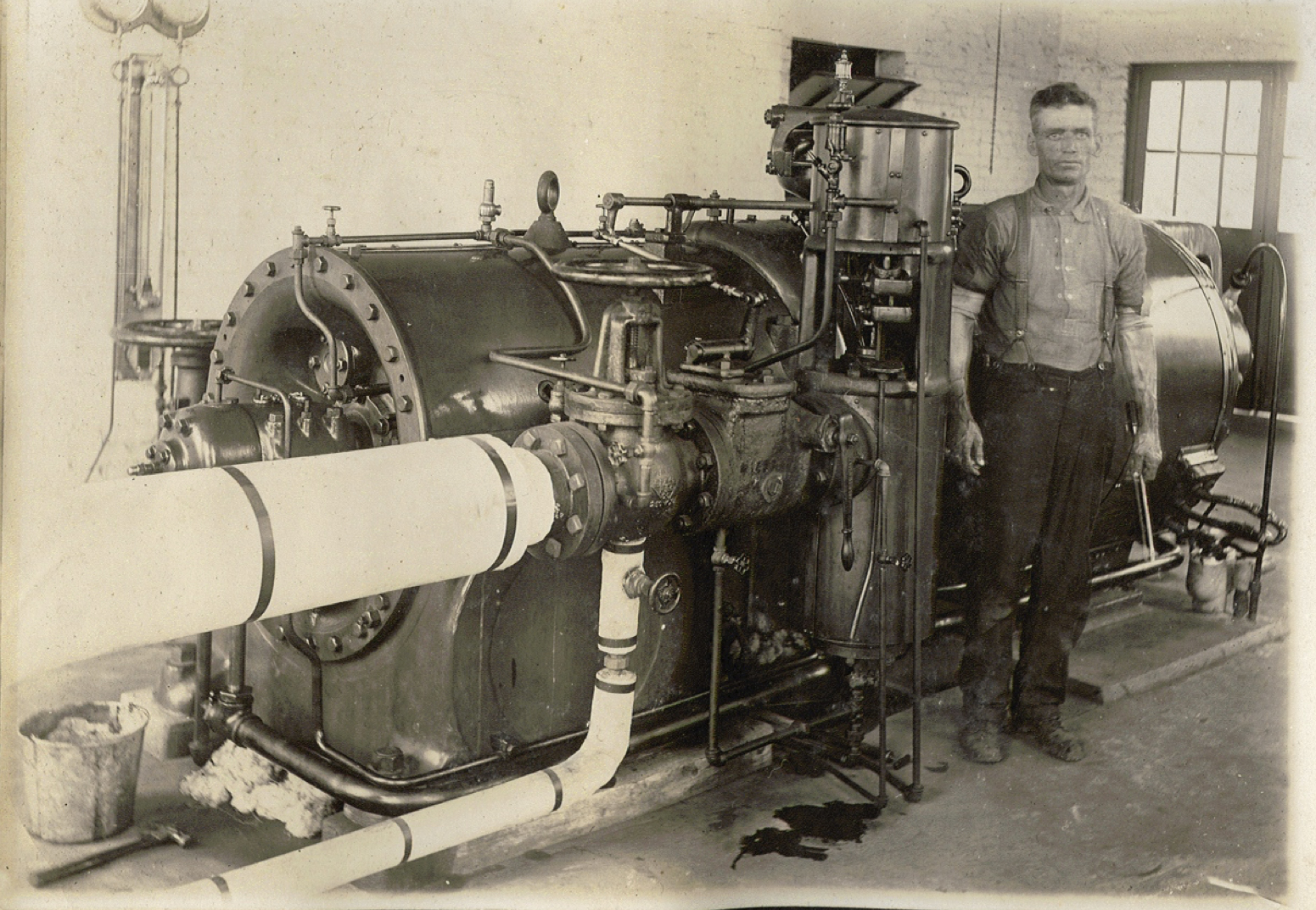

All major Franklinville utility services were initially provided to village residents by the textile mill corporations. Generation of electricity began in the mill in October 1896, when a dynamo was attached to the waterwheel and “tallow candles and kerosene lamps became a thing of the past.” Gradually nearby residences were connected to the system, which was expanded up to the World War I era so as to serve the whole community. In 1921 the mill built a large new coal-fired steam turbine generating plant which could supply power to the entire Town. In 1923 the mill signed a contract to link its system to the – Power Company of Moncure, one of the early segments of what became Carolina Power and Light system. Electric power is provided to the Town today by Duke Power.

In 1898, a deep well and steam-powered pumps began to supply the first running water system in the mill, and wells soon were drilled all over town to supply water to clusters of houses. The 1972 plats prepared of the Randolph Mills property showed 11 individual wells serving groups of residences, in addition to three wells located around the mills and a large well located on the school grounds. These wells continued to provide communal potable water until the passage of the bond referendum to fund construction of the municipal system in 1976. The mill corporation began treatment of wastewater in the 1950s as part of an expansion that built the bleachery and dyehouse necessary to print plaid flannel cloth. A expanded system was designed and built by the engineering firm of L.E. Wooten and Company in 1961; that system was expanded jointly by the mill and the Town in 1967. This treatment system was purchased by the Town in 1994; its condition had greatly deteriorated by the lack of maintenance during the mill’s period of bankruptcy from 1977 through 1985. A $1.2 million grant awarded by the Clean Water Management Trust Fund in the spring of 2000 allowed the Town to begin construction of a completely new treatment plant. This innovative, modular, 200,000-gallon-per-day plant can be expanded as needed to more than a million gallons per day- enough to meet anticipated demand throughout the study period.

Information and communication services have always been both private and public operations. The first public library in Randolph County was the one begun in Franklinville at the instigation of mill owner John W. Clark in 1924. The John W. Clark Public Library is now a joint venture of Franklinville and the Randolph County Public Library system. A telegraph connection to the outside world followed construction of the railroad. Telephone service was first provided to the Town privately in the 1920s, by extension of the lines from Asheboro. A cable television franchise was granted to Cablevision of Asheboro in 1985. Local internet connections were available through three separate private service providers beginning in 1995.

Law enforcement was one of the original functions of Town government. The Mayor was legally a Justice of the Peace, and entitled to sit with the Court of Pleas and Quarter Sessions, the antebellum equivalent of the county commission. The Town’s only employee was a Constable, equivalent to a deputy sheriff, who was responsible for collecting taxes and lost livestock in addition to enforcing local laws. A single policeman remained on the Town payroll up into the early 1980s, when the Town’s dwindling tax base and the escalating cost of law enforcement saw the closing of the department. The Town now relies on the general protection of the Randolph County Sheriff’s Department, with a satellite office located in the Town Hall. Code enforcement and administrative regulatory duties are now performed by the Town Clerk.

Franklinville Neighborhoods: Past, Present and Future

Franklinville Township was one of Randolph County’s twelve original quasi-governmental subdivisions created under the North Carolina Constitution of 1868. Based on a Pennsylvania model, each township originally had a governing body responsible for taxation, road maintenance and school districts. The governmental function of townships did not survive the nineteenth century, but townships remain as geographical subdivisions of the county. Franklinville Township took the name of its largest municipality. A seven-mile square in the central northeastern quadrant of Randolph County, it included the mill village of Worthville and the railroad crossing at Millboro in its northwest corner, the fringes of Asheboro to the southwest, the village of Cedar Falls in its center, and the Town of Franklinville in the east central portion. Four additional townships were added in 1876, and portions of what was Franklinville township are now included in Randleman and Asheboro townships.

Most of this large area is under the planning jurisdiction of Randolph County, and has been included in the county’s Growth Management Plan. The Town worked with the county in developing that plan, and to a predominant extent the goals and objectives of both the county and Town for these areas correspond. The following sections recount the separate histories and current realities for each of these areas, with notes on possible future developments. The Town of Franklinville has entered into an extraterritorial jurisdiction agreement with Ramseur which defines a line roughly following the eastern boundary of Franklinville Township as the dividing line between the municipalities. With expansion to the east thus blocked, the Town’s area for growth and development naturally lies in the areas to the west of the current city limits, and in particular along the major transportation corridor formed by U.S. 64.

A. The Village Center.

At least as early as 1801, manufacturing activity at a water-powered grist and sawmill was occurring at the falls of Deep River which would become the Town of Franklinsville. When it was incorporated in 1847, the Town included only the western mill village surrounding Elisha Coffin’s grist and sawmills, together with the brick cotton factory built from 1838 to 1840. But even then, another mill village was under construction downstream at Island Ford, where Crawford’s Path, a prehistoric trade route, crossed Deep River as it ran south toward Cheraw, South Carolina from the Great Indian Trading Path. Like Franklinsville, the village of Island Ford was situated on a hill bounded by the river and several creeks, with Mulberry Street (now Academy Street) running south down the ridge toward the ford. Both villages were laid out in a similar manner, running uphill from the riverside mills past a “Cotton Row” of worker housing; on up past the homes of tradesmen; to the larger houses of managers and stockholders scattered along the summits.

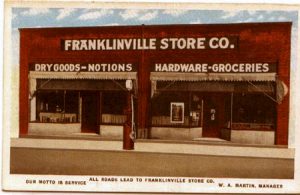

When the Town was re-chartered by the General Assembly in the 1850s the municipal boundaries of Franklinsville were expanded to include the Island Ford community, and from the mid-1870s the two villages were united in management and ownership. But they only began to assume the aspect of one town in the late nineteenth century, after the railroad depot was located at the foot of the ridge dividing the two villages and the creation of Depot (originally ‘the old Craven Road’) and Rose (originally called ‘Prosperity’) Streets allowed private homes to fill in the gaps between them. Hugh Parks, Jr., created the modern heart of Franklinville beginning in1915, when he designed and supervised the construction of a new Methodist Church, Company Office, Bank, and joint Company Store in and around the intersection of Rose, Depot and Main Streets.

The Village Center is the heart of the Franklinville Community. The Historic District which was honored by inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985 extends through much of the area. Buildings and homes unique in the state are located here, and contribute most of the character and distinctiveness that gives Franklinville any sense of identity. This area includes all the community’s civic institutions- town hall, the public library, the fire station, the elementary school, the Masonic lodge. The status of the Village Center as the historic, governmental, civic and institutional focal point of the larger community should be protected and enhanced. The higher-density pattern of nineteenth-century development should be recaptured, encouraging more intensive redevelopment of vacant tracts adjoining the historic district.

However, the geography of the Village Center which limits travel across Deep River, Bush Creek and Sandy Creek bridges will always restrict casual access to the area. It will never be a convenient or logical location for high-volume commercial development, nor do its steep hillsides and waterfront location allow for modern single-story, expansive industrial and commercial buildings. The area should be promoted as a special-purpose destination, whether for governmental, institutional or recreational uses. In this way will the area build upon its historic strengths and turn its geographical limitations into advantages.

B. North toward Grays Chapel.

Going north along N.C. 22 is nominally Franklinville for five miles or more, until one reaches the Grays Chapel area. This region was the primary agricultural backbone of the rural area serving the mill villages along the river. The areas bordering N.C. 22 and are still undeveloped agricultural lands, although the areas along Carl Allred Road to the west and Kidd’s Mill Road to the east are experiencing considerable residential growth. The Old Liberty Road corridor through Gray’s Chapel is becoming one of the most heavily-travelled highways in northern Randolph County. The Franklinville mail delivery routes extend north throughout the Millboro and Grays Chapel areas, specifically covering the Mack Lineberry, Bruce Pugh, Bethany Church, Mamie May Road communities which extend west almost to the Worthville and Randleman extraterritorial limits. Despite the postal connection these areas have more realistic connections to the Randleman area; little if any of the area north and west of Old Liberty Road should be counted within the Franklinville planning jurisdiction.

The Cape Fear and Yadkin Valley Railway which ran along the river from Ramseur through Franklinville, turned north at Cedar Falls and paralleled N.C. 22 all the way to Climax, where it joined the main line of the railroad running from Mt. Airy to Fayetteville. The railroad was abandoned in 1981, and the tracks taken up in 1985. The rail corridor is still visible along the west side of N.C.22, one of the more scenic rural thoroughfares in the county.

The Randolph County Growth Management Plan classifies most of the area immediately north of the Town as a Rural Conservation Area, promoting traditional agricultural operations, forestry and open space uses which protect the rural character of the region and discourage significant residential development. Due to the elevated grade that would require water line booster pumps, the Franklinville Capital Improvement Plan does not anticipate the construction of water and sewer lines in this area more than half a mile north of the current city limits. These limitations on development would also correspond with the Town’s plan to make the Village Center a special purpose destination, with the agricultural region to the north becoming a contrasting rural gateway to the historic center and commercially-developed U.S. 64 corridor.

C. Cedar Falls and points West.

The neighborhood around York’s Pond, Middleton Academy and the Ironworks on Bush Creek made up the western boundary of nineteenth-century Franklinville. The Cedar Falls community a mile farther west and upriver, is also, like Franklinville, made up of two separate mill villages, Cedar Falls and Sapona. These villages have always been distinct from the Town of Franklinville, and have been proud to distinguish themselves from it. But the suburban pressures of the late twentieth century are blurring the traditional distinctions. Cedar Falls students have attended school in Franklinville for more than forty years, and the Sapona area is already within the extraterritorial jurisdiction of Franklinville.

For planning purposes it is assumed that the Cedar Falls community, and the Blue Mist community on its southern edge at US 64 will form the western boundary of Franklinville in the future. North of Cedar Falls the Wicker-Lovell, White’s Memorial, Carl Allred and Old Liberty Road areas blend into the Millboro community east of Randleman and west of Gray’s Chapel. All of the area immediately north of Cedar Falls is considered a Secondary Growth Area by the county Growth Management Plan; transitional residential development is permitted with scattered major subdivisions. Demand for extension of water lines into this area within the next twenty years is expected, not only west from Franklinville but east from Asheboro and southeast from Randleman. This area is poised for further residential growth from all three directions, and will undoubtedly become one of the county’s key residential areas.

Construction of the “Southern Loop” interstate bypass road has created a natural dividing line between Asheboro and Franklinville at the foot of Trogdon Hill and Gabriel’s Creek. Asheboro water is currently available to Loflin Pond Road, with Franklinville water lines still some two miles east. Future connection between these two systems, in addition to extension of the Franklinville sewer system west, will undoubtedly attract intensive industrial and commercial development to the area. The two gasoline filling stations at US 64 and Loflin Pond Road are now within the extended city limits of Franklinville, having petitioned for annexation after the Town’s successful alcohol referendum in 2016.

D. South of Deep River.

To the south of the Town lay separate neighborhoods traditionally divided by the forested ridge behind Faith Rock. “South Franklinville” was the community at the south end of the covered bridge, southwest of the center of Town, on the road which ran south towards Spoon’s Mill and the Raccoon Pond. Near the end of the bridge was the blacksmith and wagon shop of the Jones family. There also was once located the Fairmount Methodist Protestant Church (now destroyed), and is now the location of Franklinville Pentecostal Church, as well as Chimney Lane Church and Academy. The road to Asheboro originally led from the covered bridge through this community southwest, meeting Iron Mountain Road and US 64 at Pleasant Cross Church. The iron mine on Iron Mountain Road was traditionally the far southeastern corner of the greater Franklinville community.

Southwest of the center of Town, south of the steel bridge over Island Ford was the “Gold Bowl” community, so-called after the Gold Bowl gold mine southeast of Faith Rock. Demolition of the steel bridge in 1969 isolated that part of the city limits of Franklinville which is located on the south bank of the river. The road south from the steel bridge originally connected directly to State Road 1003, Pleasant Grove Church Road, running due south into the heart of farming country in Grant and Coleridge Townships. The present-day road past the Randolph Mills lakes and around the back of Faith Rock, originally known as Wagon Wheel Road and now known as Faith Rock Road, was built in the early 1970s. A small African-American community was located on the hill above Faith Rock up to the 1960s.

The Franklinville mail delivery area extends south along State Road 1003 (Pleasant Ridge Road) all the way down to Grantville Lane, including West Jones Street and Brooklyn Avenue Extension all the way to the Ramseur city limits. Confusingly, the Deep River Haven mobile home park and the K&L Western Store, both located on U.S. 64 just west of the Deep River bridge, both have Ramseur mailing addresses. Franklinville rural delivery extends west from S.R. 1003 to Foxfire Road, where Asheboro mailing addresses and telephone numbers begin.

Both of these areas south of the Village Center are counted are Primary Growth Areas by the county Growth Management Plan, due to their location along the U.S. 64 corridor. The combination of major transportation access with water and sewer availability makes the mile-long corridor from the Deep River bridge west along U.S.64 the Town’s primary short-term (5-year) growth focus. The Town extended water lines from Ramseur and sewer lines from its treatment plant to the Deep River Haven area in 1996, and engineered the major sewer outfall line to encourage development of the U.S. 64/ Pleasant Ridge Road intersection as a major commercial focal point. Industrial uses are also should be encouraged to locate along this corridor, making maximum use of the Town’s water and sewer infrastructure investment. Over the next twenty years, commercial development will inevitably extend further west along U.S.64 toward Asheboro; as water and sewer services push in that direction, the municipal boundaries of the Town will grow toward the Blue Mist intersection. The bulk of the Town’s non-residential growth over the study period will undoubtedly occur along this corridor, with residential growth clustered between the highway and Deep River.

E. East of Sandy Creek.

To the east, the Patterson Grove Church Road forms a convenient dividing line between Ramseur and Franklinville. The residents of this area have long-established ties to Franklinville through institutions such as Old Salem Church, a defunct Methodist Protestant congregation whose cemetery is now owned and maintained by the Town. The invisible cultural boundary between Ramseur and Franklinville is crossed somewhere just east of this road, as the site of the Civilian Conservation Corps camp on NC22 near Duckworth-Cox Road is normally considered part of Ramseur. In one of the Town’s antebellum corporate charters, the Franklinville city limits extended all the way to the mouth of Sandy Creek at Deep River. This was later changed, but today the point where the U.S.64 bridge crosses both Deep River and Sandy Creek provides a mental dividing line between the extraterritorial jurisdictions of Franklinville and Ramseur.

N.C. 22 is the major transportation link through this area. During the Town’s recent Thoroughfare planning process, residents in this area expressed their overwhelming preference for continued residential development. One major determining factor which supports low- to medium-density residential development here is the Sandy Creek Reservoir shared by Ramseur and Franklinville. The entire Sandy Creek basin north of the dam is designated as a Watershed Critical Area in the county’s Growth Management Plan, and the regulations necessary to protect public drinking water supplies will curb major subdivision activity. However, this would not preclude development that might incorporate major areas of open space such as golf courses, pastures and forested buffer zones. An exception which will undoubtedly expand is the existing major manufacturing plant owned by Ramseur Interlock, located on the west side of Patterson Grove Road just north of N.C. 22. The area around this intersection is relatively level and already has available water utility lines; it should be targeted for further commercial, and perhaps industrial development.

South of the reservoir’s dam the watershed regulations do not apply, and more intensive subdivision development should be encouraged in areas with access to water and sewer infrastructure. Buffer zones must be left along the Sandy Creek and Deep River flood plains, where no development except for recreational uses should be allowed. The former Cape Fear and Yadkin Valley Railway right-of-way, which followed the river, could be improved into a regionally-significant greenway and hiking trail system. Running from U.S. 64 at Sandy Creek and Deep River all the way through the Village Center and west into Cedar Falls, the trail would become the recreational backbone connecting all the traditional neighborhoods of the larger Franklinville area.

[1] NC 22 follows the course of an ancient “ridge road” established in prehistoric times, and threads between Bush and Walnut Creeks with no major fords. At their closest point just east of Moon Mountain, the road threads through a pass between the two watercourses that is just over 500 feet wide.